By Anthony Bain

During the cold months of winter and spring, the North of Spain can be a place of unmitigated isolation. Los Picos de Europa (The Peaks of Europe) mountain range is an unwelcoming place this time of year. The jagged, deeply fissured mountains straddling the Northern province of Palencia are rumored to be the first thing sailors saw when returning from the Americas. The mountains loom out over the horizon like something out of Game of Thrones. There are remote villages amongst the peaks that are cut off for months at a time, running off of coal heating and the food they have collected during the autumn months.

Exploring Guardo

The Village of Guardo at the foot of the mountain range used to be a mining town; however, nowadays it’s another working class town making ends meet in a time of economic uncertainty. An abandoned viaduct welcomes me into the village. The construction company left when the financial crisis hit, and in this part of Spain it hit hard. Various buildings lie half constructed and forsaken — I could be forgiven for thinking that it looks like a natural disaster has hit the area.

It’s a Friday, and the weekly village market is under way. This is where people get local produce from surrounding areas. Garlic is an important part of the local diet here, and vendors have set up stalls selling them for a Euro a string. Another stall sells gourmet seafood preserves in cans, a holiday season food staple. Next door they are selling bread by the kilo, infused with nuts and olives. There are also vendors selling wines from the surrounding areas. Just to the South of the province of Palencia are the Rueda, Toro, Tierra de León, and Cigales wine valleys. The most popular red wine mainly comes from Ribera de Duero, lesser known than neighboring La Rioja. With its acutely hot summers and bone chilling winters, Ribera de Duero produces an intense red wine that marries well with Northern Spanish dishes.

Head to these #Spain mountain villages for delicious #food and #wine. Click To TweetLa Hora del Vermut

The aperitif hour here is known as La Hora del Vermut. It represents the hour just before lunch or dinner and is a social ritual in this part of Spain. Each village has its own route of bars, a culinary journey taken by the inhabitants of village. Moreover, every bar has something special to offer and a different wine to wash it down with. Families and friends venture out to their favorite taverns to partake in freshly prepared plates of tapas. It’s an ingrained tradition; it’s how they interact with each other socially once the working day is over.

In the villages of Palencia, you pay for the drinks while the tapas are always complimentary. This is tradition that will never change, a custom which has been largely (and conveniently) forgotten in the rest of the country. All the bars are well within walking distance, most of them nothing more than a stone’s throw away from each other.

An Immersive Food Crawl

I start at La Chuleta, a den-like hunter’s bar with low ceilings and boar heads mounted on the walls alongside photos of local legendary hunters. The customary Caldo soup is simmering away in a cauldron on a hotplate. Spanish Caldo, a soup made from various pork parts and chickpeas infused with smoked paprika, is a perfect winter accompaniment for the bracing cold. I’m told in confidence from the barman that in Palencia no part of the pig is left over once it has been killed, and the Caldo soup is brimming with unrecognizable but tasty pork meat.

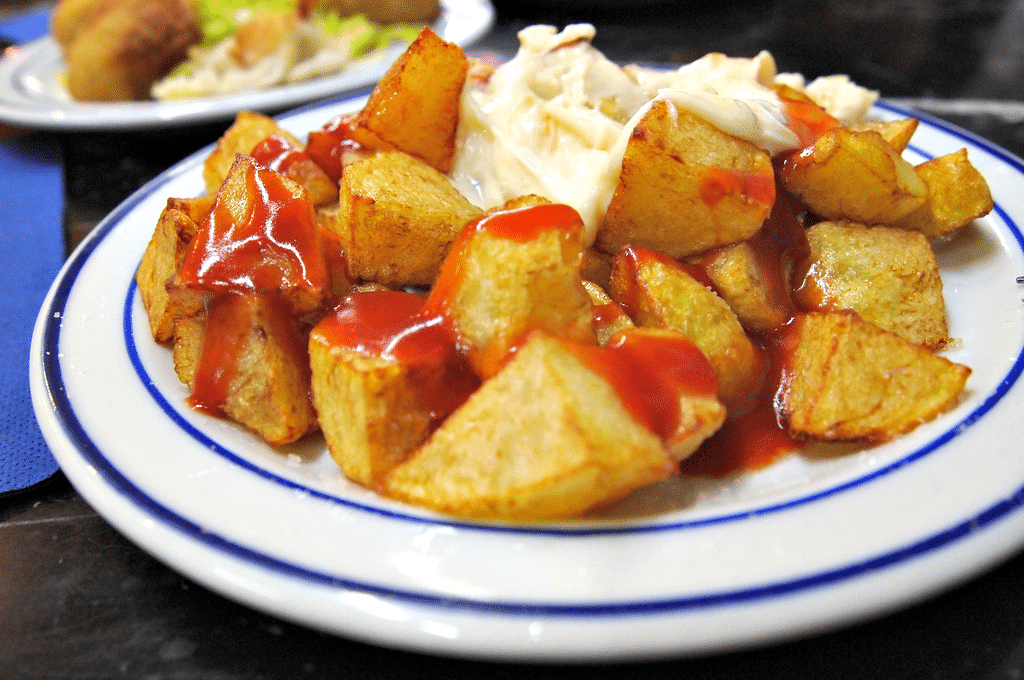

La Chuleta is also famous for its patatas bravas, mountain potatoes cut rustically and baked, then fried and served with a home-made chili sauce. The sauce is not for the faint hearted but popular with the locals, warming them up on stone cold nights. The owner is the sauce maker and the sauce is a family secret. In fact, many bars in the area have tried to copy it without success. I order vino peleon the generic name for strong red wine that is hand pressed from local bodegas by people around the village, using a cooperative grape buying scheme. It’s called Vino Peleon because it’s a hard ruddy fighting wine, famously guzzled by Ernest Hemingway. I feast on Torreznos, deep-fried pork fat served with salt, made using the fat from the wild boars that live in the mountains, eating acorns from the vast forests of Oak.

Fans of #tapas and #wine will #love these hidden #local #bars in the #north of #Spain. Click To Tweet

The route continues at Mesón el Portalon, a bar perched half way a mountain. At the fireside we are served plates of locally produced smoked chorizo on rustic bread; morcilla, a blood sausage which is slowly cooked over a grill and served with a garlic soup; and setas; locally hand-picked mushrooms from the surrounding mountain forests. The owner usually serves toasted bread with honey to accompany the soup, but he informs me that a few months back a bear attacked his beehive and made off with his honey stash.

About The Author: Anthony Bain

After studying at the London School of Journalism. Anthony Bain has spent the last 12 years living in Barcelona and sharing his writing about the city for such publications as The Barcelona Metropolitan. He has also published short stories for Papertape magazine and Ky Story. He has recently been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and his first travel book Wanderings Along the Camino will be published in late 2016. You can read more of his work on Contently.

What are some of your favorite places in Spain for tapas and wine? Please share your experience with us in the comments below!

Recommended:

Pure Paradise: Six Eco-Friendly Beach Resorts In Europe [Blog Inspiration]

Tapas Recipes: The Little Dishes Of Spain [Great Reads]

Clever Travel Companion Pickpocket-Proof Garments [Travel Safety]

Latest posts by Anthony Bain (see all)

- 7 Unique Dining Experiences You Can Have In Barcelona - Jan 10, 2018

- How To Explore Craft Beer In Marlow, England - Jan 31, 2017

- Hunting Out The Best Wine & Tapas In Spain - Nov 7, 2016