By Trang Pham-Nguyen, Epicure & Culture contributor. In this article, she tells one of many stories of Vietnamese refugees, this one about her father.

In 1973, Vietnam was far from an idyllic place to live.

Unless you were friends with the Communist government officials, you were guaranteed to live in poverty regardless of how smart or talented you were in school. Some were even too poor to afford education or a simple bag of rice. Many families lived in tiny shacks, with humid weather that fostered the infestation of mosquitoes.

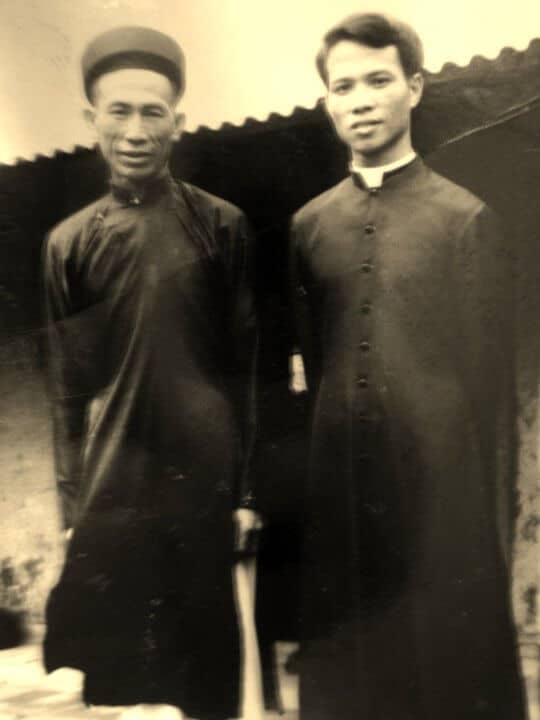

During this time my father, Hien, ran for his life and hid in the forest from the Viet Cong Communists.

Now, this was not the first time he tried fleeing Vietnam and it wouldn’t be his last. His first attempt was unsuccessful; but as Hien returned home he was already making plans for his next escape.

At that time, the communists were strict and brutal. Many people attempted to flee the country and escape the government’s tyranny.

Hien had a year left before he finished his studies to become a Catholic priest.

The communists didn’t allow many people to practice their religion, and most seminarians — my father included — were forced to work for them.

The Viet Cong Communists promised these seminarians cushy jobs that paid well; however, it turned out to be the opposite – poor pay and highly laborious jobs. A small bowl of rice was their only meal for the day.

At first, Hien’s family didn’t know where the government took him. His youngest sister, Nhieu— just 15 years of age at the time — walked up and down local streets each week asking for him.

Nhieu learned Hien was working just outside of town. When she found him, he was scooping out mud from the bottom of a lake; orders from the communists. She hardly recognized him, his face gaunt and his body looked famished.

The sight of her exhausted brother upset her. When Nhieu returned home, all she could do was cry.

Years later, Hien again decided to flee Vietnam and escape the oppressive conditions of the country.

Electricity and phones didn’t exist yet, and the majority of people lived in poverty, including Hien’s family. Being the eldest son of eight children, he hoped to one day flee to the United States where he could earn a living and make enough money to support them.

Hien attempted to escape Vietnam nine times with a small rowboat that had a tiny motor attached to the end of it.

The first time Hien was caught, he was jailed for three months.

When he was released, Hien walked home donning tattered clothing and a torn rice hat, with long hair and a grown-out beard. Hearing a knock at the door, his father was confused to find a young man covered in bumps and lesions.

Not recognizing him as his son, he shooed Hien away, believing he was a beggar. When Hien’s parents realized it was him, they burst into tears.

A Life-Saving Message Received

Every time Hien was caught trying to escape, his jail time increased:

Six months to nine months, and then one year.

At that point, he could only be let go if someone posted bail.

Although his parents were desperate to help him, they had very little money.

His mother asked her daughters to sell the little bit of jewelry or gold they owned. She walked along the streets, begging to borrow money from strangers to help her son.

If ever an inmate was released from jail, Hien seized the opportunity to contact his family, asking the newly released prisoner to deliver a note.

Upon receiving a message, Hien’s father would pack a small stash of dried foods, with some extra for the inmates in case Hien needed their help one day.

His father had to take a bus or walk an entire day to get there. The majority of the time, the prison was located far away from home.

When Hien’s father arrived, the soldiers searched him to make sure he couldn’t sneak anything in.

As he had expected this, he hid the note carefully inside a boiled sweet potato. The note read, “Whatever happens, do not admit guilt.”

This was to warn Hien from admitting guilt for it may lead to a permanent life in prison.

That message kept Hien strong and he never confessed to any crime, even when the guards beat and tortured him for an entire week.

What Life Was Really Like Inside Vietnam’s Prisons

Conditions at the prisons — or labor camps — were inhumane.

Clothes were never provided. Their showers were water hose spray downs, given only once a week.

Prisoners were required to work 1000 square meters — the size of a baseball diamond — of the rice field every day. They were punished if they didn’t finish the job.

My father’s jail cell was the size of an 18’ x 18’ room, or the size of a standard bedroom. Sixty men were squeezed into this tiny room with him.

There was no space to lie down so they slept back to back or against the wall.

Sometimes Hien was squeezed into the corner where there was a hole in the ground filled with urine and fecal matter, some of it splashing against his face when someone had to relieve themself.

“Let’s escape tonight. We can cross the river and jump the fence,” suggested a priest inmate, imprisoned for practicing his faith.

Hien not only refused, but also tried to convince the priest that it was too dangerous. The priest went anyway.

The next morning, the Viet Cong called for Hien to bury something. One of the guards dragged a lifeless body out from the utility truck.

It was the priest.

The guard handed Hien a shovel and ordered him to dig a hole, large enough for the body. Hien later learned that while crossing the river, the priest lost his glasses; his vision was too poor for him to find his way out.

When the Viet Cong found him, they shot him. Hien requested to mark the grave of his friend, but the officer struck his back with a rifle gun.

My father told me, “I’ll never forget that pain. I’ll never forget those days I was in prison.”

Hien’s Ninth & Final Escape Attempt

The ninth time Hien was caught trying to escape, he was put in prison for three years. With no word from their son, his family believed he was dead.

When Hien was released, he met a man named Duong, who had been spying on the Viet Cong for months. Duong had learned their schedules, when they rotated shifts, and, most importantly, when they weren’t watching the gates or the border.

The reason Duong was watching things so closely:

He was formulating a plan.

Actually, Duong was building a ship to escape on, and invited Hien to join him.

There was a cost, of course, and the payment amount was much more than many Westerners could afford in the 1960s, let alone locals in a poor country like Vietnam.

But this was a vital journey that needed to happen. Hien’s family put together their entire family savings and sold all their valuables — including the little jewelry they had — to pay Duong.

What was terrifying was there was no guarantee this would work, and Hien’s family would not get their money back if it didn’t.

Freedom Doesn’t Come Easily

Of course, many people were so desperate to flee the country that they took the risk. Hien’s family had enough money to send only him, the eldest son seen as the head of the family after their father; his parents and siblings had to stay behind.

Over a hundred people — men, women, and children — squeezed onto the boat.

They cheered when they were able to past the gates and finally escape the borders of Vietnam; however, stormy seas lay ahead, making many of them very ill.

While out at sea, a large fishing ship approached them.

Thai pirates.

They swarmed the refugee boat, raping and killing the women, tossing their bodies and their murdered children out to sea. Any men who tried to fight back were killed and thrown overboard.

Out of 120 people, only 15 men survived.

The pirates took the remaining men — including Hien — to another Vietnamese boat they had looted. It sat drifting in the middle of the ocean, and the pirates left them there for a week without food or water.

These surviving men resorted to collecting rain water with a plastic tarp and stored it in an empty gas tank, not knowing how long they would be stranded or when the next rainfall would come. Taking only a few sips per day, their bodies grew weak from hunger and dehydration.

Eventually they could see land about a mile off shore in the distance, and Hien knew that he had to muster all his energy if he wanted to survive. Grabbing one of the empty gasoline tanks, Hien jumped into the water.

He wrapped his arms around the tank for support praying that he’d stay afloat, closed his eyes, and began to kick his feet.

Out of the 15 survivors left who swam, only 10 made it to shore.

Fortunately, the remaining survivors were found and put into a local refugee camp.

Hien moved around to different camps, including ones in Indonesia and Hong Kong.

He was only 25 years old at the time.

The Destination Reached

Eventually he was sponsored by an American, and arrived in the midst of the cold winter in Connecticut in only a t-shirt and shorts.

With no knowledge of English reading, writing, or speaking skills, he felt alone and miserable.

Hien didn’t have the opportunity to go to school, as he immediately went straight to work to cover expenses like a car and groceries, while also sending money back home to his hungry family in Vietnam.

He continues to do so to this day.

This is one of millions of refugee stories, which I’m a product of. Growing up, I never knew much about my parents’ background besides the fact that they met in America, as my mother had also escaped the Viet Cong and came to the U.S. I never knew their journey and their history

My history.

While taking a year-long trip through Asia, I stopped in Vietnam and paid a visit to my father’s family.

Here, I learned about his past.

Visiting my roots helped me not only understand a piece of the world better, but also my parents and where they came from.

Now I can grasp why they kept drilling me to perform well in school and to get a stable job; it was so I didn’t have to grow up in the poor and difficult conditions they once did.

The stories of my father, the hardships he endured, and the resilience he carried to survive all odds in coming to America inspires me to triumph through rough times in life, even when I can’t see a light at the end of the tunnel.

It’s been a grateful and humbling experience to see the struggles they’ve gone through to provide me a better life, which in turn gave me the opportunity to travel, opening my life to new cultures, experiences, and stories to share with others, just like you.

Do you have other stories of Vietnamese refugees to share? Reactions to the above account? Please do so in the comments below!

Enjoyed this post? Pin it!

Latest posts by Travel With Trang (see all)

- How My Father, A Former Vietnam Prisoner, Escaped To The USA - Jun 17, 2018