Interview By Katie Foote (Epicure & Culture Contributor); Answers by Chivvis Moore

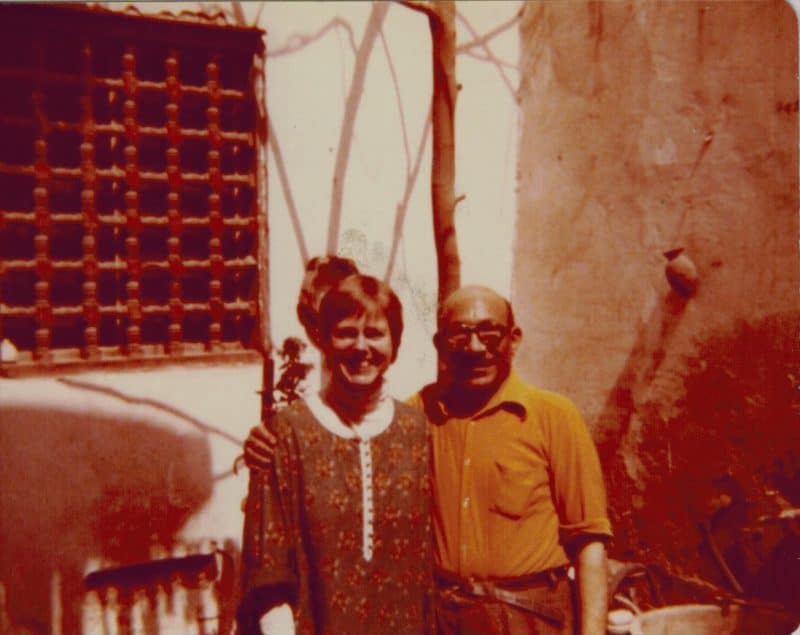

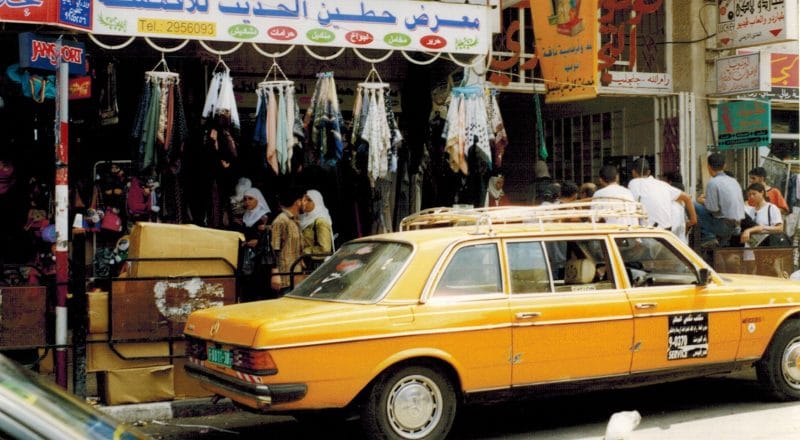

Living in Brazil as a child sparked a desire in Chivvis Moore, an American lesbian, feminist and author, to learn about other places and cultures. Inspired by a book about an Egyptian architect, she booked a flight to Cairo, though knew little about the culture and religion of this predominantly Muslim country. From there she had the opportunity to work in Egypt, Syria and Israel before teaching at Birzeit University in the West Bank. The entire trip through the Middle East lasted 15 years.

Her book, First Tie Your Camel, Then Trust in God, explains her experience to people who can’t comprehend why an American LGBT female would desire such an adventure. She writes,

Why, I was asked, would I want to live in an Arab country? Don’t Arabs hate the United States? Don’t they resent our freedom? Don’t they all want to kill us? Aren’t I afraid? Surely a woman traveling alone can’t want to live in a Muslim country—considered by definition a misogynist society.

I understand why people ask these questions. I see the same news they watch each evening on television. I read the newspapers they read. To the French women of that evening long ago, to other Europeans, and to my fellow US citizens, this book is my effort to answer these questions and others I have been asked.

For those of you who don’t have immediate access to the book, Moore agreed to share some of her experiences with Epicure & Culture through an exclusive interview. She describes daily life, navigating her identity, interacting with men and other women in the Middle East, and gaining a better understanding of Muslim culture (hint: the answers may surprise you).

Before visiting the Arab World, Moore earned a BA from Harvard University and worked as a journalist. She has also earned her living as a carpenter and general building contractor, an editor and researcher, and a teacher of English for Academic Purposes.

1) What first drew you to the Arabic culture and Middle East?

I first decided to go to an Arab country in 1978. I made up my mind after reading a book by the Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy, where he described building houses of mud brick for poor people. I was working as a carpenter, and wanted to volunteer on his projects. In those days US citizens were just as ignorant of Arab and Muslim culture, but there was not the violent anti-Arab and Islamophobic rhetoric there is now.

2) A lot of people are deterred from visiting because of myths about how women are lesser beings. Did you take any of this seriously enough to think twice about visiting?

Egypt brought to my mind pyramids, tombs and hieroglyphics. I had heard almost nothing about Arab or Muslim women, and our country was not yet using the myth of the repressed Muslim woman as an excuse for war. So no, these were not concerns of mine before I went.

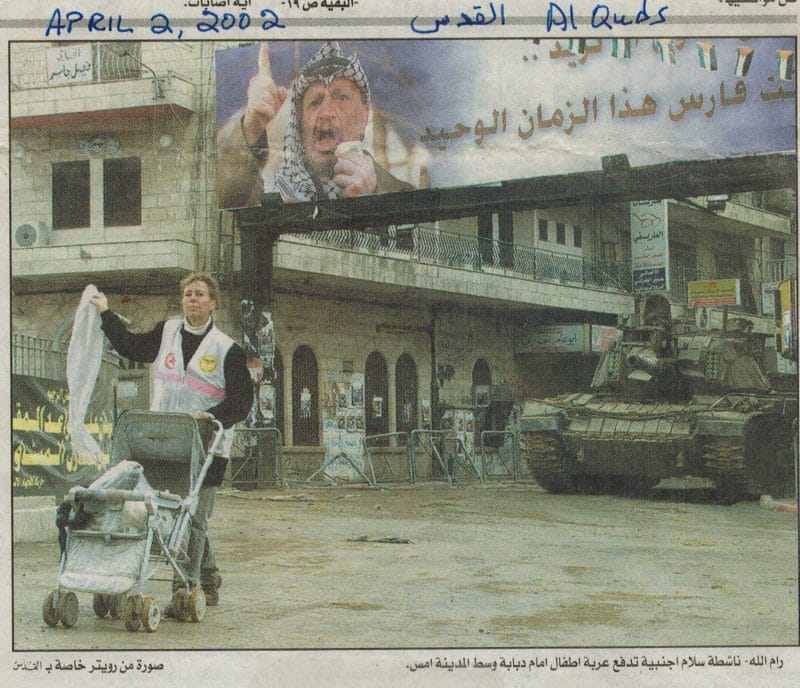

Returning to the Arab world in 1992, I already expected to love wherever I went. I had known when I left Egypt that I would want to return to learn which of the strands had attracted me so: did I love Egypt primarily because of special qualities that country had? Would I love any Arab country? Any Muslim country? I went because my life had opened in a way to allow it, because I had chronic fatigue and knew that among Arabs I would find emotional sustenance, and because I wanted to understand more about the situation in both Israel and Palestine. Although I went first to Syria, my ultimate destination was to be Palestine.

3) In the book you talk about how foreign women avoid the gender classification that local women are expected to follow. Did you find this awkward or empowering?

Any time I felt myself being treated differently from local women I had to look at what this meant. When I was invited to eat with men while the women ate in another part of the house, I had to look at why. Would the women of the house have preferred to be eating with the men and their guest? I doubted it. I was always aware of a lively, self-contained women’s world existing in another part of the house. When I was allowed to join this part of the household, I always found it warm, informal, animated. I suspected that the women, given a choice, would have preferred, just as I did, eating in one another’s company to eating in the formal dining room.

On the other hand, I was allowed to work in the carpenter’s shop, as the carpenter’s daughter would not have been. This was clearly unfair and – yes – awkward. And it was, of course, simultaneously empowering: as a result of my special status as “foreigner” I received the gift of learning this craft. Had my life been like that of many Egyptian woman – consisting of preparing food, caring for children and running a household, perhaps while also working in an office, bank, or school — I would have found that about as easy as I would have found such a life in my own country; that is, not easy at all.

Here's why your view of #MiddleEast culture may not be correct #women #culture Click To Tweet

4) In your experience, what ways are Muslim women freer than Western women?

In my opinion Muslim women are freer than Western women in not being expected to show their bodies in scant or revealing clothing, in not feeling they are socially “out of it” if they don’t have sex before marriage, in not having to date. I felt trapped in my own culture when I was a young woman, feeling pressure to do these things.

Some, though not all, Muslim women are free also in having a home and social life mainly with other women, and in living in extended families, as opposed to the closed male-dominated nuclear family in which I grew up [where] a child no adults other than her own parent(s) from whom to draw support. I am aware, however, that extended families also have their drawbacks.

The roots of the first group of characteristics come from Islam, a religion that calls for what is termed a certain “modesty” in dress and sexual behavior from both women and men. The extended family tradition, although for many reasons this is changing in many Muslim cultures, was once fairly universal throughout the world. The nuclear family – the term was coined only in the 20th century — appeared in Western Europe and New England as late as in the 17th century, under the influence of the Christian church and theocratic governments.

5) Did you experience any sexual harassment or discrimination based on your gender while abroad?

As a lesbian who lived 16 years in three different Arab countries with Muslim majorities, I can say I never encountered any prejudice directed at me. But the whole issue of sex is far more private than it is in the West; it’s hard to figure out who is gay. Even a heterosexual Muslim couple will not hold hands, much less kiss, in public; and certainly I was never asked about my sexuality. Also, while I would not have feared for my physical safety had I been “out,” I did worry that those who cared about me would reject me socially if they knew I was a lesbian. And it was clear that any intimate relationship I might initiate with an Arab woman would put that woman at risk of approbation in her own society.

Growing up in the United States I felt tormented as a teenager and a young adult knowing I was a lesbian. I accepted society’s judgment: I considered myself “abnormal” and mentally ill. It was not until I was in my late twenties and living, first in Mendocino County and later in the San Francisco Bay Area, that I fully accepted my sexuality and came out as a lesbian. Acceptance of gays and lesbians is a very recent phenomenon in the US. I think that kids growing up in the Middle East feel the way I did and experience the same disapproval from parents and rejection by peers that we in my generation suffered in the US when we were young and that LGBTs still suffer in many places in the US.

I think it’s interesting that in the Arab world, with the exception of territory occupied by ISIS, action against LGBTs comes primarily from governments. On the other hand, in the US today repression comes most in acts of individual violence. Trans people, in particular, are being attacked and killed across the US today.

6) In Egypt, you talk about hiding the lesbian side of your identity to respect the culture. Could you ever live openly with this in the Middle East?

In Syria I was told that a foreign teacher had been expelled from the country for being gay. In the West Bank I heard that a foreigner was fired from Birzeit University for the same reason. But although many Muslim countries have laws on their books punishing gays — and heterosexuals for sexual activity outside marriage — I never heard of those laws being implemented. A certain town in the West Bank is referred to quite openly as a town with many gay men. And in 2007 Palestinian lesbians inside Israel held their first public conference, and lesbians from the West Bank attended, with no retaliation.

I told close friends, those who had lived for a time in the U.S. and who I guessed would be accepting. It did seem to me that several of my colleagues went out of their way, through comments they made, to let me know they had no problem with my sexuality. I could have made it clear I was a lesbian, but I probably would not have been able to teach in schools or universities if I had.

The #Truth About Living In The #MiddleEast As An American Lesbian #Feminist Click To Tweet

7) What is the Muslim view of homosexuality and where does it come from?

There is no “Muslim view” of homosexuality, any more than there is a “Muslim view” – or a “Christian view” — of anything else. Most Arab countries still have laws on their books that restrict sexual freedom. Some of these laws, interestingly, date to colonial days, when Arab societies were seen as perverted in the eyes of their Western colonizers. Lebanon, for instance, criminalizes what it calls “sexual intercourse contrary to nature” in a law derived from the French mandate period [i]. In Saudi Arabia, the US government’s principal ally in the Middle East, a married man engaging in sodomy or any non-Muslim who commits sodomy with a Muslim can be stoned to death. All sex outside of marriage is illegal. [ii]

But laws vary across the Muslim world. As in the Christian world, the laws of each country have been and continue to be made mostly by men, who have created the laws as they saw fit. There is not one monolithic body called Islam, any more than there is one monolithic Arab point of view, which is consistent over time and across the region. Beliefs of ISIS and more conservative versions of Islam, like that in Saudi Arabia, are not representative of most of the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims. I have gay and lesbian Muslim friends and know other Muslims who want no part of it. In Islam there are many points of view and many interpretations of the religion’s two scriptural sources, the Qur’an and the traditions of the Prophet Muhammad.

8) How do Islamic texts dictate actions for/against homosexuality?

There are passages in Islamic texts that clearly favor heterosexual marriage, and there are certain passages in the Qur’an (4:15-16 and of the story of Lot), along with a collection of inconsistent ahadith [iii] that condemn sodomy. But the same thing is true of both the Christian Bible and the Jewish Talmud; and I personally know quite a number of Muslim gays and lesbians who, like LGBT Christians and Jews, regard the homophobic texts of their religion as irrelevant to their standing before God.

I know no culture where parents rejoice to learn their children are gay, and particularly not boy children. In patriarchies like those existing now in Arab countries and in the US the nuclear family is primary, with boy children expected to carry on the family name. There are Arab parents who tell their gay sons to keep it quiet, but they don’t kill them — despite the frenzied insistence to the contrary of a woman who interviewed me recently for a radio show.

Interestingly, according to a 2015 Pew poll, American Muslims are more accepting of homosexuality than evangelical Christians, Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses, and more likely to support same-sex marriage than US evangelicals, historically Black Protestants, Mormons and Jehovah’s witnesses. US Muslims are just about as likely to support same-sex marriage as Christians generally. [iv]

9) What aspects of gender roles in the Middle East are changing most quickly?

The Arab Spring was an expression of widespread desire for democracy and freedom from tyranny of all kinds. As Arab societies throw off the oppression of their authoritarian rulers and their foreign backers and invaders — foremost among them the USA — I believe we will see great changes in Arab and Muslim countries.

It might be that the gay and lesbian roles are changing most quickly, although I’m certainly no expert. In the West, gays and lesbians often define themselves by their sexuality. We say we are “gay and proud,” we group together, work for gay rights, feel our tribes are those whose sexuality resembles our own. Arab society does not seem patterned along these lines. Whether Arabs who are drawn to gay and lesbian sexual orientations will begin advocating for rights and define themselves in terms of a sexual identity will be interesting to see.

Women in the Middle East are working to expand women’s rights in every arena, just like women in the US, in India, and across the globe. I am sure that there will be significant advances in the Arab and in the broader Muslim world as women interpret their religions in ways that make sense to them and work toward goals reflective of their own desires. I expect there will be many differences from Western feminisms – possibly, for example, less concentration on individual rights and more emphasis on the wellbeing of the community.

Do you have any personal experiences to add to Moore’s account of culture and women in the Middle East? Please share in the comments below!

And make sure to check out Chivvis Moore’s book, First Tie Your Camel, Then Trust in God, and visit her website, ChivvisMoore.com.

Citations:

[i] “What Does the Koran Say About Being Gay?” Mehammed Amadeus Mack, in Newsweek, June 15, 2016.

[ii] “Here are the 10 countries where homosexuality may be punished by death” The Washington Post, June 13.

[iii] hadith, (plural: ahadith) a collection of traditions containing sayings of the prophet Muhammad

[iv] “Stop Exploiting LGBT Issues to Demonize Islam and Justify Anti-Muslim Policies,” by Glenn Greenwald, The Intercept, June 13, 2016.

Katie Foote

Latest posts by Katie Foote (see all)

- 8 Outstanding Conservation Safaris Around The World - Apr 12, 2022

- These 10 Women Whiskey Distillers Will Make You Crave A Manhattan - Dec 12, 2018

- Ethical Travel: Should You Visit Thailand’s Long Neck Women Villages? - Dec 9, 2018

- 8 Pioneering Vegetarian Vacations Around The World - Aug 13, 2018

- A New Perspective: Can Travel Help Reverse Alzheimer’s? - Aug 5, 2018

Really interesting interview. I appreciate the window into another culture, into a place I’ve not experienced. Thank you for this interview!