Travel isn’t always pretty. Intrepid traveler and wildlife volunteer Shara Johnson tells us about an eye-opening and somewhat difficult experience working at the Uganda Wildlife Education Center, as well as how to experience local culture, what to eat, and why both good and bad realities are worth exploring.

1. You spent a month in Uganda volunteering with the Uganda Wildlife Education Center, the country’s only zoo. Please tell us about that experience.

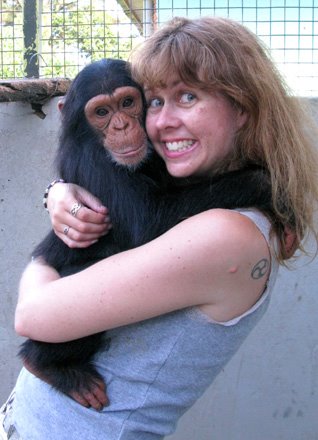

Most of the animals in the UWEC have been brought there as rescued animals, as opposed to being born there or purchased. But the organization has no training or facilities for rehabilitating the animals back to the wild, so most remain there in habitats open to public viewing. As a volunteer, you basically just work alongside the zookeepers to care for the animals and their habitats and night enclosures. Not very glamorous work, but it affords the opportunity to be in very close quarters with the animals. I had particularly wanted to spend my time with the chimpanzees, so I worked primarily in the chimp house, mostly preparing food for their meals and snacks and then feeding them.

2. What were some of the adjustments you had to make living on the zoo grounds?

I had a very comfortable flat at the far end. I guess the primary adjustment was getting used to the animals that roamed around and made noises throughout the night. I was warned about the cobras and mambas that were known to live on the grounds. Once, a marabou stork came by and stole a piece of chicken right off my plate as I was eating dinner. The biggest challenge was dealing with the large population of vervet monkeys who roam the grounds, some of whom could be aggressive. I eventually learned their schedule and knew when they would and wouldn’t be hanging out along my path to home. If I ate off site and was carrying leftovers home through the grounds, I really had to be careful not to get harassed by them. That being said, I took a heck of a lot of adorable photos of them. But I loved walking by the shoebill stork’s marshy habitat at night when the frogs and insects were stupendously loud. And lying in my bed listening to the lions roaring and the chimpanzees get all riled up from time to time was something I enjoyed.

3. You mentioned to me the zoo experience was a conflicting one, and it opened your eyes to many Third World Country realities you hadn’t previously considered. Can you tell us more about this?

A big conflict for me was that this is a facility that many would condemn for its primitive conditions, and after being privy to some of its shortcomings not visible to the general public, I felt very frustrated and disappointed. I thought, “Do I really want to be supporting this organization?” But the truth is, it’s the best there is at the moment in Uganda, primarily because it’s the only option for orphaned, injured and abused wildlife to be rescued and given an opportunity for a healthy life, albeit in confinement. Ngamba Island is a dedicated chimpanzee rescue facility — much more state of the art — which is an offshoot of the UWEC because the UWEC began receiving more chimps than they could handle. But they take only chimpanzees. UWEC staff will travel literally across the country to retrieve an animal if somebody calls them and says they need a rescue. I think that’s admirable.

Unfortunately, the staff has very limited knowledge in caring for a lot of types of animals, as unlikely as that sounds. I saw them literally Googling on the insanely slow internet connection on the staff computers how to take care of some of the animals they were receiving. Many of the zookeepers have a real heart for the animals and most attended the country’s wildlife training institute; however, the quality of the education and skills just isn’t commensurate with the realities of working in the rescue zoo. Many of the keepers didn’t choose a career in wildlife — it would take too long to explain the somewhat unfortunate education system — but suffice to say, this was not their chosen field. While most of the habitats are quite nice with lots of lush natural environment, the animals sometimes are inadequately cared for, not out of malice, but from ignorance or through a chronic lack of proper supplies and equipment.

The lack of supplies and equipment flabbergasted me at times and was disheartening. But in a country like Uganda, raising money from the government and private donations is more complex than it might seem. Take volunteering as one example. In perfect honesty, the reason I chose to spend time at the UWEC rather than another more competent and state-of-the-art rescue facility/center is because it was pretty much the only one I could afford. One month at the UWEC costs a fraction of what it costs to volunteer for one week on Ngamba Island or some place like Chimp Eden. You might think, “Well, why doesn’t UWEC raise their volunteer contribution fee to raise more money?” They could, but who in their right mind would pay the same price to work in a low caliber facility as they could to work in a high caliber one? Kind of a chicken and egg. Anyway, it comes to a question of is it better to deny support to a facility run at significantly less than optimal conditions, already lacking funds for any significant animal enrichment items, the denial of which will only result in the animals ultimately suffering even less optimization, or to give what support you can to help conditions as much as you can, knowing this is currently the best thing available. I decided to believe the latter. I also in the end decided to buy some supplies, some enrichment items for the chimps, and to pay to repair a broken tap.

4. What were some of the issues you learned about working in the Uganda Wildlife Education Center?

The importance of tribal affiliations and cronyism, for one thing. And people looking out for themselves financially. Not that this doesn’t happen in every corner of the world, but in a poor country with high unemployment rates, it’s a whole different ball game. It’s the kind of thing I’ve often read about through others’ experiences; it was eye opening to confront it myself, though — and with people I personally knew. And frankly, it stripped away a lot of judgments I might have otherwise imposed upon these situations looking at them from the outside. (To be sure, refraining from judging is not the same as excusing.)

I also wrote an essay published in The MacGuffin about how the animals are treated better than some of the people. I know I’m painting something less than a rosy picture here, but if you’re really interested as a traveler in knowing the world, all realities — both good and bad — are worthy of exploring.

I learned about priorities and ingenuity — if you have few resources, you learn how to use them in amazingly creative ways. I’ve seen photos and passed by things along roadsides or sidewalks that illustrate this creativity, but it was interesting to witness it on a daily basis and to have people look at me like I was pitiably dimwitted when I didn’t think to use something in an unconventional way.

One thing that often broke my heart is that my friends there understood how far behind the First World they are. They aren’t living in isolation thinking this is as good as it gets, that they are living in the crux of modernity. They have access to see what the rest of the world is like, they spend time with Westerner volunteers who tell them about our world, and they are perfectly cognizant of their more unfortunate situation, but feel helpless to affect any change and hopeless that it will happen of its own accord.

5. What was the most rewarding part of the volunteer experience?

Well, this may seem painfully obvious, but just getting to spend time in close quarters with the animals, which is precisely what I expected to do, was the real reward. My favorite thing to do was to get to the chimp house before anyone else was there in the morning and go to the back of the night enclosure where it’s open to the air (the chimps spend daytime on a lush island) and hang out with the chimps; I could interact with them a little through the caging. One of them loved to play with my tennis shoes, for example. And feeding them their porridge in the mornings was a lot of fun. 6. What was the biggest challenge of living and volunteering in Uganda?

I didn’t find anything culturally challenging. Interesting, but not challenging. So this might sound trivial, but lack of electricity was a fair challenge. Not because I can’t survive without it, I actually greatly enjoy rustic situations without services/amenities; however, I like to be prepared for that. In Uganda I was consistently handed the impression I would have the basics, such as electricity, so I packed for and made expectations on that. Rolling power outages were incessant at the UWEC, lasting for hours and hours at a time and were utterly unpredictable, so things like recharging equipment, getting online, entertaining one’s self at night, were made more difficult. To the frustration of the zookeepers, it also made it impossible to operate simple devices such as egg incubators or to have the lights on while they’re trying to work at dusk … my “problems” were petty compared to the adverse effects on the zoo. Traveling later, the outages proved to be countrywide; I just tried to be thankful for the interludes of working power. While I was couchsurfing in another part of the country after I finished volunteering, I not only didn’t have any electricity but no running water either, for which I was totally unprepared … my host neglected to mention this void. I hadn’t even showered the morning I left to meet him, figuring I’d do it there, and I was set to spend 5 days with him.

7. What advice would you give someone interested in volunteering at the Uganda Wildlife Education Center but nervous to sign up?

Well, I imagine anxiety might be based on a concern for whether or not they will be able to do the tasks. The zookeepers are friendly and helpful and pretty insightful about what you are best suited for … if something is too difficult, simply tell them. Also, feel free to contact me personally for more comprehensive advice. I’m trying to walk a line here with being honest about the conditions, but truthfully, this was one of the best experiences of my life, so I hope my honesty doesn’t discourage anyone.

8. For travelers wanting to experience local culture, what’s one must-have experience?

That’s a hard one. I think there are probably a lot of cultural opportunities that I unfortunately didn’t take advantage of. Mostly I just hung out with individuals and learned culture through them, but that’s difficult for the typical traveler passing through. One interesting urban experience I had was watching a soccer match at a movie “theater” in Entebbe. (Please note the quotation marks, and you’d have to ask a local to find it or know it existed.) Outside Entebbe, I thought it was terribly worthwhile to hook up with a private guide through the lower Rwenzoris where I met a witch doctor and walked around the Crater Lakes, which is where I saw the fermenting bananas (referred to in next question) … tourist industry is still relatively small in Uganda and particularly in somewhat off-season (I was there in April and May) so it’s easy to get a guide to yourself and they have a very informal relationship with both you and the locals – for example, the fermentation shed wasn’t like an official stop on a tour or anything, my guide was just leading me higgledy-piggledy through banana fields (more like a banana forest) to a waterfall and noticed a fellow napping outside his home nestled in the banana forest, and asked this guy if he could show me inside his shed.

9. For travelers wanting to experience the culinary culture in Uganda, what’s your recommended food and drink pairing?

Well, culinary culture in Uganda is pretty basic. Typically you have your base food of something bland but hearty such as matoke – mashed, cooked bananas – or cassava, then a topping of meat and broth. The base food varies by region, and many people literally live on just that base. When I asked friends what their favorite food is, they nearly always said one of these basic foods, which is surprising to me. I found them intolerably bland, but if you want the real traditional food, that’s what you should have. The broths, however, are invariably quite tasty and flavorful and can be made with beef, chicken or fish.

As a volunteer at UWEC you’ll be fed lunch each day, which consists precisely of what I’ve just described. Street food is usually simple but good, typically kabobs of goat meat or chicken, and delicious chapatti. Being a tropical country, there are many delicious fruits and vegetables. My favorite was jack fruit.

Uganda has a surprisingly large and tasty selection of beers, mostly lagers, which go well with the basic food. I’m a dedicated beer drinker, so I always enjoy trying all the beers when I travel. I was surprised by the large selection. My favorite was Nile Special. The cultural specialty is a liquor made from fermented bananas. They are special bananas different from and smaller than eating-bananas. I saw some of this liquor being made near Fort Portal, as referenced in the previous question. I can only say that if you try it, you are braver than I am. I won’t describe the scene I saw in the shed, but the visual combined with the olfactory sensation quashed any bravery I might have had to try it. I asked several people if they liked this drink, and every single one stated an emphatic, “No!” And yet it is widely drunk in many traditional ceremonies.

10. What was one unexpected experience you had and loved while traveling in Uganda?

Well, there were a number of them, but I guess the Couchsurfing experience alluded to above was pretty unexpected. Clearly I expected to stay with this person, but I was unprepared for not only the complete lack of facilities but also for the amazing insight I would gain into the typical rural existence, attitudes, and knowledge of the wider world (that is to say, a lack of knowledge — for example, I was consistently asked if we have stars in the sky at night in America).

I’ve Couchsurfed in other countries so I had some expectations, but this far exceeded them, as I stayed in a mud hut on the grounds of a primary school founded by my host, and spent evenings around a campfire talking with him and his secondary-school teacher friend (who also asked me about the stars). The school mistress led me on a walk through the area where a tourist would never go or be welcomed, introduced me to people and experiences a regular tourist could never have. It was not the situation I expected, but it was fully awesome.

*All photos courtesy of Shara Johnson

About Shara

Shara Johnson plots her travels abroad from her home in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, where she also hosts other travelers as an airbnb host. You can follow her adventures abroad at SKJtravel.net, next destination is Iran, April 2014. Friend her on Facebook or follow her on Twitter (where she regularly tweets photos of the UWEC chimps).

Jessica Festa

Latest posts by Jessica Festa (see all)

- A Culturally-Immersive Adventure In Mongolia’s Altai Mountains - Jul 8, 2023

- This Recipe Sharing Platform Supports Women In The Culinary Industry (Labneh Recipe Included!) - Nov 5, 2020

- Hiking The Mohare Danda Community Eco-Trek In Nepal - Jun 3, 2020

- 6 Important Questions For Choosing A Responsible Yoga Retreat - May 18, 2020

- How To Create & Grow A Profitable Blogging Business (Ethically) - Jan 18, 2020