By Jessica Festa, Epicure & Culture Editor

Crazy fact: Did you know there are only a handful of fresco painters left in Florence?

Cool fact: Did you know you can paint a fresco with one of them during a 2-hour Florence art class?

On a recent trip to Italy, I was searching through options for Florence art classes. In the end, I had the pleasure of doing a fresco-painting workshop with the amazingly talented Dr. Alan Pascuzzi through Context Travel, a global company focused on taking travelers below the surface of a destination.

Dr. Pascuzzi’s studio is located in the artisan-focused San Frediano neighborhood, on the “other side” of the Arno River — aka opposite the Duomo.

The quiet streets here showcase artist studios, wood-working spaces, antique shops, leather-makers, small cafes and, of course, Dr. Pascuzzi’s workspace.

As soon as I walk in I’m in awe of the many sculptures and paintings lining the walls, his talent immediately apparent.

Actually, he is the only one of the local fresco painters who uses classic techniques, not even relying on photographs for his commissioned pieces. Instead, he paints from real life.

Tip: Want more Italy travel? Scroll all the way down to see my boyfriend and I’s trip video, showcasing Venice, Florence, Tuscany, Umbria, the Amalfi Coast, and Ischia!

Psst, don’t forget to pin this post for later!

History Of Fresco Painting

I’d always thought “fresco” referred to any mural painted in a church; however, it’s actually a style involving painting on damp plaster with water-based pigments.

As the plaster dries the pigments become part of the matrix of the plaster due to a chemical reaction.

So yes, frescos can be murals — and usually are — but not all murals are frescos.

While we think of Renaissance notables like Michelangelo, Diego Rivera, and Fra Angelico as the earliest fresco painters, in reality, we can credit this to indigenous cave painters.

Additionally, there are frescoes still around since the Minoan civilization of Bronze Age Crete (2000-1500 BCE).

Of course, these early peoples had no idea they were paving the way for an explosion of culture to be born, especially in Greece and Italy.

While they were looking to spread ideas among their own community, their cultural influence rings true even today, especially in the Florence workshop where I’m sitting.

The Art Of Fresco…

Typically frescos are created on walls, though for the workshop we practice on a rectangular terra cotta roofing tile.

It works like this:

A mixture of plaster, sand and occasionally marble dust is applied to the work surface in three coats, though the final coat is painted on before it dries.

To ensure accuracy when painting, the artist creates a cartoon — not the Bugs Bunny kind, but actually a word deriving from the Italian “carta,” or paper.

The cartoon is transferred to the plaster and the painting begins — and finishes — before the plaster dries.

This is buon fresco — or “true fresco” — different from “fresco-secco,” which is painting on dry plaster with pigments mixed with a binder.

…And the Science

There’s also a science to buon fresco — literally.

There is a chemical reaction that occurs when natural dry-powder pigments like charcoal and ground-up gemstone touch wet limestone.

Explains Dr. Pascuzzi, “You take marble, burn out the carbon dioxide, mix it with water and basically make it into a marble paste. You mix this with sand and make mortar. The marble paste loses the water — as in, it dries — but it regains the carbon dioxide from the air.”

This means it slowly turns back into marble; but before it does, you paint on it with water-based pigments that get absorbed and then trapped in the hardening mortar.

When it dries it is a piece of marble with pigments in it.

Pro tip:

These beautiful masterpieces also make for great slow travel souvenirs from Italy.

Racing The Clock

As noted above the painting must be completed before the plaster dries — including the final tempura layer added.

This means that not all of the great Renaissance painters were also great fresco painters.

Of course, Michelangelo proves himself with the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel; however, while Da Vinci was a great artist, his attention to detail made fresco painting difficult for him because he needed more time.

In fact, while working on the Last Supper he added his tempera to already dry plaster. Because of this the paint began to come loose just two decades later.

Sheesh, if Da Vinci found frescos challenging, how would I fare?

Preparing For Fresco Painting

The great thing about the workshop is Dr. Pascuzzi takes the class step-by-step, so even if you’re not the world’s greatest artist (gulity) you’ll still leave with something worthy of hanging up.

Dr. Pascuzzi also lays out an array of pre-selected pigments — white, black, red, yellow, green blue, brown and indigo, a few made by combining other hues.

Unlike your childhood watercolor set, this setup includes just a few natural pigments that are solely mixed with water — no binders, like oil, are added.

When we get to the blue color, he pauses and pulls a small blue tube off his shelf. He explains it’s Lapis Lazuli from Afghanistan — not the blue we have on our palettes, but the blue used in the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel.

“Just 10 grams costs about 100 Euros! The amount used in the Last Judgement used millions of dollars worth of Lapis Lazuli.”

Even without the costly color, the world fresco is our oyster, as we can easily blend these natural pigments to create violet, sky blue, and skin tones.

We’re also given boar’s hair brushes — one thick for backgrounds and large areas, one thin for details — which works well against the “sandpaper” of the fresco as it absorbs.

Before painting we dip our large brushes into a water bucket, plopping droplets onto the hues. It’s essential to keep the pigments wet.

Again, in buon fresco there is no binder, but instead the lime in the plaster helps bind the pigments using just water.

Our image choices are between Mr. Lenzi and Mrs. Lenzi, two donors who commissioned a fresco work by Renaissance painter Masaccio.

Mr. Lenzi wears a red cloak with a head covering that bends his ear and shows his neck, while Mrs. Lenzi wears a dark blue cloak completely covering her head and neck.

Each portrait showcases lots of contrast between shadows and highlights.

Florence Art Classes: Fresco Rewards The Bold

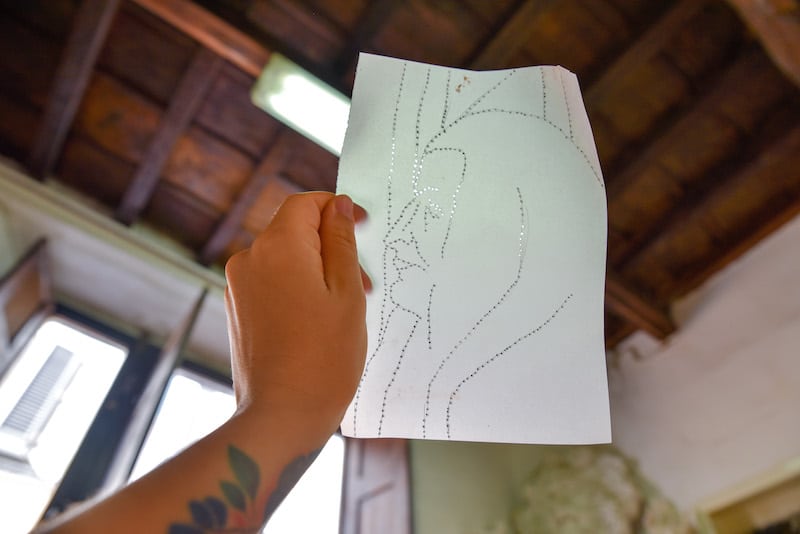

I opt for Mrs. Lenzi, and start creating my cartoon, using sticky tack to bind her picture to the tracing paper. This helps me pencil-trace my subject without the paper moving all over.

Once traced, I affix the tracing paper onto a Styrofoam board.

Using a long tool featuring a pin mounted in a holder called an awl, I poke small holes along the traced lines, the pin-pricks sounding like raindrops and putting me into an almost meditative state.

“Imagine doing this for three days straight?” smiles Dr. Pascuzzi.

He then lets us know we need to shut off the fans. “This is because we want to give ourselves more time to paint, and the fan takes moisture out of the air.”

This shows just how much climate and season can play a part. Along with stopping air circulation in the room, working on wetter days — vs a hot and dry August morning — would also give you more time to work.

We’ll have about an hour.

“Fresco rewards the bold and punishes the tentative,” smiles Dr. Pascuzzi, reminding us that it is truly a creative race against the clock.

While we’ve been creating our cartoons Dr. Pascuzzi has been spreading the mortar — one part lime paste mixed with one part fine sand — on masonite, preparing the surfaces on which the group will be painting.

He places a square in front of each of us, instructing us to gently touch the mortar’s center with one finger.

Explains Drs. Pascuzzi, “We’re seeing if it’s dry enough yet to paint on. If you see little white particles on your finger it means it is still too damp to work on. If your finger is slightly ‘spotted’ with water it means that the water is being pushed out and it is almost ready to paint on. If it is damp but firm it is ready to paint.”

Adding Some Color

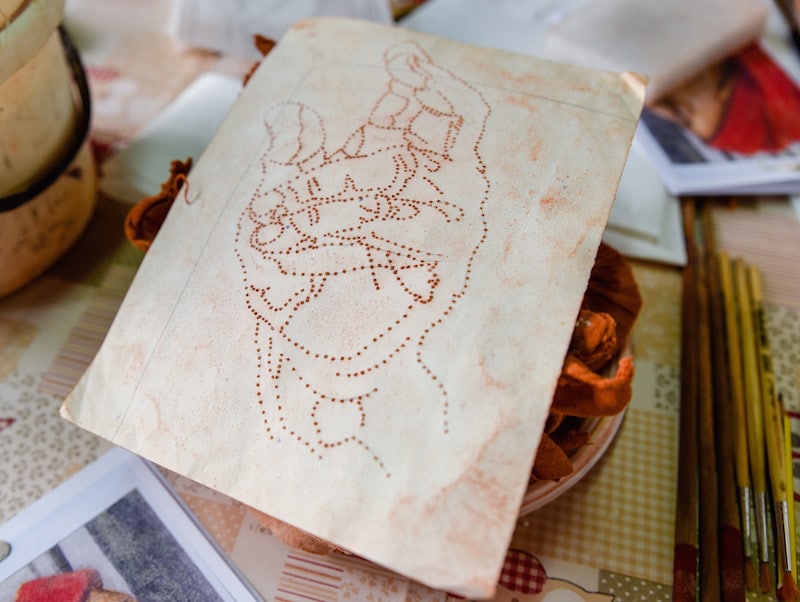

Next it’s time to add some color; not with paint, but with a red ochre- filled powder puff.

With a partner gently holding down the pricked tracing paper, I “pounce” it with the puff, a burnt red dusting gowning the workspace.

When I’m done and my partner’s fingers are lifted, the paper edges naturally roll up, clearing the mess of powder to reveal a perfectly dusted outline of Mrs. Lenzi.

Finally, it’s time to put paint to plaster, by first tracing the dusting with red ochre paint to create an outline to work with.

“You’re looking for a soy sauce or tabasco consistency,” explains Dr. Pascuzzi, as we mix the water with the paint. Being liberal with the water — you really can’t use too much — I introduce the pigments to the plaster surface, letting the lime do its thing.

Dr. Pascuzzi smiles. “I love seeing how everyone’s individual styles begin to come out.”

This is the last time I use my thin brush for a bit, as when painting fresco it’s smart to do the large areas first. Smaller details are trickier, and you’ll want to spend more time on them.

Blue and brown are mixed on my palate to create purple, and I choose a downward stroke to stick with as I draw thick purple lines down the plaster, following the ochre as a guideline.

Between these lines goes light purple, and I add some white to my purple to create the violet color.

Next, I move to the shadows and highlights of Mrs. Lenzi’s cloak, mixing bright blue with brown, then adding some white to the mix for the highlights.

To blend the contrasts a technique known is “scumbling” is used.

This refers to softening the lines or colors, which adds a more natural look.

Finally, defining lines are added with a thin brush using dark brown. While at this point you can still see some of my red ochre lines, Dr. Pascuzzi says it’s no sweat. I can wait for it to all pull up and go back to it later.

When the painting is complete, the artist (me!) isn’t done.

Now, it’s time to touch up our work — though with modifications to our paint mixtures.

In fact, as time moves on it’s important to use less water and add a bit of extra white.

Notes Dr. Pascuzzi, “As the mortar dries it does not absorb water as its porosity decreases.

If your pigment is too watery it beads up and can ruin the mortar.

When almost dry you have to help the pigment along a bit and sometimes add a little white which is made of lime paste.

This is only if the fresco is almost dry and not usually done.”

An Ancient Tradition Continues

The difficult thing for Dr. Pascuzzi is that, despite his immense talent and passion for keeping traditional fresco painting alive, many people want things quick and cheap.

While Renaissance artists like Michelangelo and Fra Angelico were revered, today’s tech-obsessed culture — even in Italy — has led to shorter attention spans.

“Speaking in general terms, fresco began to ‘decline’ when artists realized that there were other mediums to use to do large paintings,” explains Dr. Pascuzzi. “Oil paint was one and also tempera paints — pigments mixed with a binding agent. These were easier to use and allowed artists more time to work.”

He cites da Vinci’s Last Supper in Milan as a good example of artists trying to get around the problems of fresco.

Leonardo did not have a good idea of what he was doing and the painting began to fall off the wall.

“The other factor in the decline of fresco was the change in the types of commissions,” continues Dr. Pascuzzi. “Fewer churches wanted big fresco cycles and the need for large permanent works on walls simply declined. Fresco was relegated to decorative schemes on the ceilings in private homes or big villas.”

A Passion Continues

Dr. Pascuzzi considers fresco to be the hardest painting technique to use since you do not have a lot of time.

“To do a good fresco you have to know how to draw well, and also be very secure of your painting skills. If you do a fresco correctly you can be sure that it will last forever — plain and simple. It is a technique that puts the artist to the ultimate artistic test: if you can do a good fresco then it means you are in a very small group of artists who reached that level of mastery and ability.

This is the challenge every time I do a fresco — and there is an immense satisfaction in completing a large fresco work. It puts you close to the level of Michelangelo and the other Renaissance masters. That is why I love it.”

He continues, “This is also why I can wait between commissions. When someone asks me for a fresco it means they understand it and are worthy to have one done for them. It is a skill that is ancient, and it is extremely satisfying to know that I am carrying on an ancient tradition that spans from the Etruscan tomb painters to the Greeks, to the Romans, early Christians who painted in the catacombs to Giotto, Masaccio and to Michelangelo. It is like being part of art history. I may be forgotten in the future; but, I know my frescoes will still be there.”

Looking for Florence art classes? Want something unique to do while exploring with friends or traveling Italy solo?

You can help support Dr. Pascuzzi’s mission to keep traditional fresco methods alive, while creating a meaningful trip souvenir for yourself, in this exclusive Context Travel experience.

What Florence art classes would you recommend? Please share in the comments below!

Logistics:

Getting There: Santa Maria Novella is the main train station of Florence (locally called “Firenze”).

Trains: I used Omio to book all of my Italy travel and found the site not only easy to navigate and in English, but also often cheaper than actually booking through TrenItalia or Italo (the train lines I used during the Italy trip).

Note: Make sure to book early if not using a Eurail pass! You’ll save money the earlier you book.

Getting Around: On foot! Florence is very walkable. They also have taxi service, though note they cannot be flagged down. Instead, you must go to a taxi station or call them. Here is full information on this.

Currency: Euro

Dining Tips:

- Understand that in many places there will be an extra charge for sitting at a table.

- Note that you do not need to tip — service is typically included — though you can leave 5-10% if you wish.

- While in the US if a restaurant serves a snack that was not asked for, like bread or peanuts, it’s safe to assume it’s complimentary. In Italy though we were often charged a few Euros for these. If you don’t want them, say so.

Language: While many locals speak English, it’s helpful to know some Italian. At least know a few common words and phrases.

Accommodation: I found Airbnb to be really affordable with tons of great options — many with views, gardens and patios. Get $40 off your first Airbnb with this link.

SIM Cards: While you can buy your SIM card from the airport, I recommend purchasing it within the city of your first stay. This way, if there’s a problem you can go back to the place you actually purchased it to get help.

I sadly purchased mine from the Milan Airport, and wasn’t told you’re supposed to *not* use your phone until you receive a certain text message (which is in Italian). I used up my entire 40-Euro package — which should have lasted my entire 10-day trip — in less than an hour due to this error and had to re-purchase one, because the Vodafone representative in Venice (the first city visited on the Italy trip after landing in Milan) told me the airport wasn’t affiliated with his shop.

Footage taken by Jessica Festa & Andy Pilc; edited by Andy Pilc

Jessica Festa

Latest posts by Jessica Festa (see all)

- A Culturally-Immersive Adventure In Mongolia’s Altai Mountains - Jul 8, 2023

- This Recipe Sharing Platform Supports Women In The Culinary Industry (Labneh Recipe Included!) - Nov 5, 2020

- Hiking The Mohare Danda Community Eco-Trek In Nepal - Jun 3, 2020

- 6 Important Questions For Choosing A Responsible Yoga Retreat - May 18, 2020

- How To Create & Grow A Profitable Blogging Business (Ethically) - Jan 18, 2020

I thoroughly enjoyed your post. I love fresco painting especially the combination of the craft of plastering and the art of painting. I learned a lot from your post.

Thank you.

loved loved loved this! Lived in Italy for a year and the culture is…there are no words. Thanks for sharing. Hopefully when I return I get to do this class. Thanks !

loved loved loved this! Lived in Italy for a year and the culture is…there are no words. Thanks for sharing. Hopefully, when I return I get to do this class. Thanks!